TSG 1899 Hoffenheim has been one of the biggest surprises in European football. Until recently, they were the only unbeatable team in Europe and currently, they are fighting for a Champions League spot in Bundesliga. All this while being led by Julian Nagelsmann, the youngest coach in Bundesliga history. Nagelsmann, 29 years old, is managing Hoffenheim for the second year, after being able to save them from relegation last season. When he assumed the position last year, with only 28 years old, Hoffenheim was 17th, 7 points behind safety, with 14 games to be played. The team’s progression since last season is an astonishing accomplishment, due to some of the most innovative ideas in German football.

Hoffenheim started the season playing in a high block, pressing in 1-4-3-3, Nagelsmann’s preferred system, but defensive shortcomings became apparent early on. With the team applying so much pressure on the side of the ball, the opposite side became a weakness that other teams could explore. After realizing that, Nagelsmann changed to a 1-3-5-2/1-5-3-2. That way Hoffenheim was able to keep a compact block and defend the weak side much better with a five-man defense.

Nagelsmann stands for an active positional defense, especially against strong opponents. Clogging up the central lane is a top priority, leading the opponent to the side lanes. Usually, the forwards don’t press opposing center backs. Their main concern is to cover passing lanes to the midfield, leaving the opponent with only one choice: play it to the full-backs, where the team applies real pressure and tries to recover the ball.

Hoffenheim does this differently according to the side of the pitch. On the right flank is the full-back, usually Kaderabek, who steps up to pressure the opposing full back, with Sule coming wide to cover for the Czech. On the left, there’s no one capable of doing what Sule does (so well) on the right, so the dynamics has to be different. On this side is the central midfielder (Demirbay, in this case) who pressures the full back, with Rudy coming from behind to cover his movement. Toljan, the left full back (out of the picture), stays deep and marks the opponent winger. This allows Hoffenheim to create numerical advantages in wide areas, maintaining always at least four men in the defensive line.

After recovering the ball, the team reacts to the opponent’s pressure. If it’s high, they attempt to transit as fast and as vertical as they can, to get to danger areas as quickly as possible. This move has two goals: caught the opponent off guard and limit the potential harm of losing the ball in transition. In the German league, where most of the teams adopt successfully the counter-pressing, this is very important for Hoffenheim´s success. If the ball is recovered without immediate opposing pressure, Hoffenheim slows the pace and go for a more combined type of buildup. Successful offensive transitions are one of the biggest weapons of Hoffenheim. They prefer the center lane, but they are constantly trying to occupy all channels to stretch the opponent and have more options to get to the net.

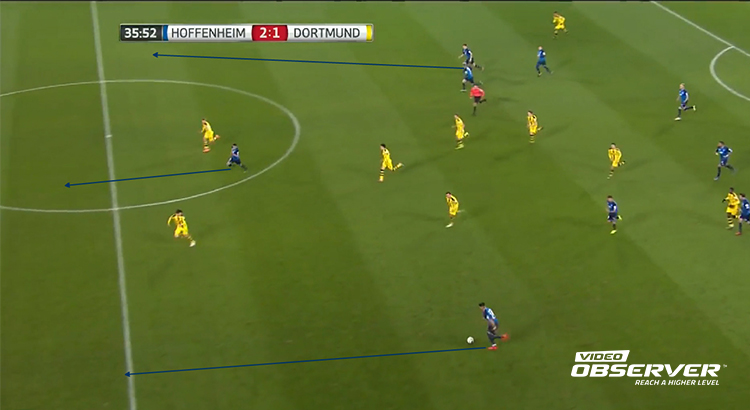

One of their most effective dynamics in transition is to alternate short pass combinations in a confined area, with long and direct passes to the opposite side, catching the opponent unbalanced many times.

When there’s no avenue to transit quickly, Hoffenheim settles in a patient build up. There’s a prominent tendency to play through the right side, due to Sule’s confidence with the ball. Once the ball enters the midfield, Hoffenheim tries to play it directly to the forwards, whom stay close together to enable short combinations after the vertical pass.

Even when there’s none passing line available at the middle, they search for a vertical pass to the wings, as long as it breaks opponent´s lines and keeps the team moving forward. As in transition, Hoffenheim alternates short and long passes in organized attack. Sometimes, one of the forwards drops to form a diamond in the midfield, allowing for short combinations. Once the opportunity arises, Hoffenheim then changes the attack focal point with a long pass, trying to explore the opponent’s’ most vulnerable areas.

This is one of Nagelsmanns’ biggest accomplishments. Hoffenheim is extremely effective with the direct attacks, mainly because of the coordination between supporting movements and forward runs. One or more players support the ball carrier, offering a short option and dragging the oponnent defenders, while at the same time, another player gets in behind. We can see this type of movement countless times.

Many teams perform similar moves, but it’s the timing that really places the opponents in a hard situation, and they do this while maintaining an appropriate shape to deal with an eventually lost ball.

All this shows the great work Nagelsmann has made. The young coach identified problems early on and created a system that is in constant evolution. It’s hard to ask more from this team. They have been performing well above initial expectations. Even if Hoffenheim fails European qualification, this season has to be seen as a major success.